February 2025

Books read:

- The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America's Great Migration by Isabel Wilkerson

- Creation Lake by Rachel Kushner

- The Air They Breathe: A Pediatrician on the Frontlines of Climate Change by Debra Hendrickson

- Canyon Dreams: A Basketball Season on the Navajo Nation by Michael Powell

Trails walked:

- West Rim trail near Taos, NM (Feb 4th)

- South Boulder Creek Big Bluestem loop near Boulder (Feb 21st)

- Lindsay Ranch in Rocky Flats National Wildlife Refuge near Superior (Feb 25th)

Song(s) of the month: Guy Clark - Dublin Blues and The Cape

February Summary:

I thought about writing a diatribe on theinsanity sadness whirlwind that is our current administration in Washington DC. There is so much I would like to say about it, and I'm having difficult discussions with my conservative friends these days. But I decided that there are way more talented people than me out there writing and speaking brilliantly about it (Rebecca Solnit, Susan B Glasser, Heather Cox Richardson, and Bill McKibben), so why add my meager two cents? Anyway, I'm sure many of you need a respite from it all. So instead I wanted to talk about a photo I ran across recently. See it below:

Things My Grandkids Say: My wife bought some really cute dessert plates that have these cartoon-like people on them with sayings about desserts they love. I love them. I gave my grandson a piece of pie on one of the plates and he asked for a different plate. Confused, I asked him why he wanted a different plate. "Because I don't like to eat from plates that have people's faces on them." The fascinating quirks of childhood.

Song(s) of the month: Guy Clark - Dublin Blues and The Cape

After several false starts over the past two and a half years, I finally got back to my guitar playing. If you recall, I dislocated my left middle finger on a hike back in September of 2022. It took probably a year for my finger to completely heal, but I was having trouble getting back into my guitar playing, mainly because the finger really hurt after playing just a couple of songs. I kept trying, half seriously to get back into it, but other things began to fill my time. These two songs are what brought me back. Dublin Blues is a heartbreaking song of remembering a past love while The Cape is an empowering song encouraging you to do what you love to do no matter what other people say. The Cape is one of the few songs I can actually finger pick well (I figured out my own picking pattern that works for me). I play Dublin Blues the way I play most songs, simply strumming chords, but the song really instills a great feeling inside me when I play it, especially in a "dark and empty room." I featured Clark's song Stuff That Works in my June 2020 blog. I started out that blog with the question, "How do you pick a favorite Guy Clark song?" You can't. He's a master songwriter who had a major influence on both the Austin and Nashville music scenes from the 1970s onwards. He passed away 9 years ago from lymphoma and it was a great loss. Enjoy.

I thought about writing a diatribe on the

That is my grandma Rose (my dad's mother) circa 1925. She was maybe 18 or 19. Her sitting on that motorcycle has an incredible story behind it. You see, she was in love; you can see it in her smile. I'm filling in a few blanks in this story because there are certain topics that weren't discussed among family in the 1920s, so not all the facts are certain. One of those taboo topics was out of wedlock children. Rose got pregnant from the owner of that motorcycle. She was ushered away from her home and all she knew to live with friends of the family while her pregnancy proceeded. This had to be hidden in those days. Tragically, Rose's lover died in an accident driving that motorcycle in the photo while she was pregnant. Who knows what happened? Was he beside himself not knowing where Rose was? Possibly. Rose had her child, a boy she named Robert. Robert was my uncle, my dad's older brother by 10 years. All my dad knew for most of his life was that Robert was his older brother and a war hero in World War II. What he didn't know was that my dad's father Ernie (my grandfather) offered to marry Rose, baby and all, to help her move on from a difficult situation. They had three other kids together, including my dad. I first met Grandma Rose when I was a year old after my mom and dad drove me from New Mexico to Boston to meet my dad's side of the family. She visited a couple of times when I was young, but the first time I actually remember her was when I was 17 and we were back east for the bicentennial celebration. Grandma Rose was beloved by all my cousins back east; they knew her as Mumu. I never really got to know her that well because of the distance, but I always thought she had the saddest smile I'd ever seen.

My rambling this month was cut short not only by a short month, but by a week long cold spell where the temperature never got above the 20s. It was frigid and I had no interest (nor clothing) to hike long distances in those temperatures. I did manage a memorable hike along the rim of the Rio Grande Gorge in New Mexico (it's a pretty good story, you should read it below), a walk in the foothills near Boulder, and a visit to an old ranch on radioactive land. My reading took me from the Great Migration of the 20th century to a spy thriller, then to a book on the climate's impact on children's health, and a finally a fun and poignant story of a season of high school basketball on the Navajo reservation. Enjoy.

Things My Grandkids Say: My wife bought some really cute dessert plates that have these cartoon-like people on them with sayings about desserts they love. I love them. I gave my grandson a piece of pie on one of the plates and he asked for a different plate. Confused, I asked him why he wanted a different plate. "Because I don't like to eat from plates that have people's faces on them." The fascinating quirks of childhood.

Song(s) of the month: Guy Clark - Dublin Blues and The Cape

After several false starts over the past two and a half years, I finally got back to my guitar playing. If you recall, I dislocated my left middle finger on a hike back in September of 2022. It took probably a year for my finger to completely heal, but I was having trouble getting back into my guitar playing, mainly because the finger really hurt after playing just a couple of songs. I kept trying, half seriously to get back into it, but other things began to fill my time. These two songs are what brought me back. Dublin Blues is a heartbreaking song of remembering a past love while The Cape is an empowering song encouraging you to do what you love to do no matter what other people say. The Cape is one of the few songs I can actually finger pick well (I figured out my own picking pattern that works for me). I play Dublin Blues the way I play most songs, simply strumming chords, but the song really instills a great feeling inside me when I play it, especially in a "dark and empty room." I featured Clark's song Stuff That Works in my June 2020 blog. I started out that blog with the question, "How do you pick a favorite Guy Clark song?" You can't. He's a master songwriter who had a major influence on both the Austin and Nashville music scenes from the 1970s onwards. He passed away 9 years ago from lymphoma and it was a great loss. Enjoy.

Dublin Blues sample lyrics:

I loved you from the get goAnd I'll love you 'til I dieI loved you on the Spanish StepsThe day you said goodbye

The Cape sample lyrics:

All these years the people saidHe's actin' like a kidHe did not know he could not flySo he did

The Warmth of Other Suns by Isabel Wilkerson – This book landed 2nd on last year’s New York Times Best Books of the 21st Century. It was also the winner of the 2010 National Book Critics Circle Award for Nonfiction. The author is a Pulitzer Prize winner and recipient of the National Humanities Medal. It took her 15 years to research and write this epic story of migration that explains so much of how the United States changed in the 20th century. She interviewed 1,200 living members of what is now called the Great Migration. That migration lasted from around 1915 (the start of WWI) until the 1970s. During this time six million African Americans fled the Jim Crow south to seek real freedom and opportunity in the North, Midwest, and West, mainly in large cities. Of those 1,200 interviews, she took 3 of them and included their stories in this great book. There was Ida Mae Gladney who fled the sharecropper cotton fields of Mississippi in 1937, pregnant and with two young children, to Chicago’s South Shore. George Starling fled to Harlem in 1945 to escape the pennies a day citrus work in Florida and also the county’s notoriously racist sheriff. And Robert Pershing Foster, a physician and war veteran, fled Louisiana for Los Angeles in 1953 so that he could practice his skill in an actual hospital which was not allowed in Louisiana in the 40s and 50s for people of his color. Just the telling of each of their harrowing escapes from the South would make for a thrilling novel. Wilkerson intermingled these three stories of bravery with the overall story of Jim Crow in the South, the war factories in the North, European immigration, and the heartbreaking discovery of continued racism and segregation in the North, Midwest, and West. Even though it was still bad, it wasn’t as bad as the South at the time, so because of all of these brave people that decided to leave, we have been gifted with people like Louis Armstrong, Diana Ross, Bill Russell, James Baldwin, Ray Charles, John Coltrane, and many many more.

Before the Great Migration 90% of African Americans lived in the South. By the end, only 50% did so. The Great Migration eventually resulted in the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s, which in turn helped to improve life for those left behind in the South (although some would argue that it’s not fully recovered yet). The Great Migration ended mainly because of those Civil Rights heroes of the 1960s. I can understand why someone would not want to read a 622-page history book, but I assure you that this does not read like a normal history book. Wilkerson’s storytelling is gripping. If you decide not to read this book, then at least check out her 17-minute Ted Talk here.

I’ve read that several high schools and universities have incorporated this book into their curricula. I think everyone should read it. It’s that good. Hopefully the book’s usage in schools survives the next four years. Here are some lines:

A railing divided the stairs onto the train, one side of the railing for white passengers, the other for colored, so the soles of their shoes would not touch the same stair.

They were all stuck in a caste system as hard and unyielding as the red Georgia clay, and they each had a decision before them. In this, they were not unlike anyone who ever longed to cross the Atlantic or the Rio Grande.

“If it is necessary, every Negro in the state will be lynched,” James K. Vardaman, the white supremacy candidate in the 1903 Mississippi governor’s race, declared. He saw no reason for blacks to go to school. “The only effect of Negro education,” he said, “is to spoil a good field hand and make an insolent cook.” Mississippi voted Vardaman into the governor’s office and later sent him to the U.S. Senate.

Fifteen thousand men, women, and children gathered to watch eighteen-year-old Jesse Washington as he was burned alive in Waco, Texas, in May 1916. The crowd chanted, “Burn, burn, burn!” as Washington was lowered into the flames. One father holding his son on his shoulders wanted to make sure his toddler saw it. “My son can’t learn too young,” the father said.

(Warning: Graphic Detail): in the fall of 1934, when George was a teenager and old enough to take note of such things, perhaps the single worst act of torture and execution in twentieth-century America occurred in the panhandle town of Marianna, Florida…That October, a twenty-three-year-old colored farmhand named Claude Neal was accused of the rape and murder of a twenty-year-old white woman named Lola Cannidy…his captors took knives and castrated him in the woods. Then they made him eat the severed body parts…Around Neal’s neck, they tied a rope and pulled it over a limb to the point of his choking before lowering him to take up the torture again. “Every now and then somebody would cut off a finger or toe,” the witness said. Then the men used hot irons to burn him all over his body in a ritual that went on for several hours. Soon afterward, it was learned that Neal and the dead girl, who had known each other all their lives, had been lovers and that people in her family who discovered the liaison may have been involved in her death for the shame it had brought to the family.

In Louisiana in the 1930s, white teachers and principals were making an average salary of $1,165 a year. Colored teachers and principals were making $499 a year…The layers of accumulated assets built up by the better-paid dominant caste, generation after generation, would factor into a wealth disparity of white Americans having an average net worth ten times that of black Americans by the turn of the twenty-first century

the truth hit Pershing, too. He stepped outside himself and considered the absurdity that he was doing surgery for the United States Army and couldn’t operate in his own hometown.

They were packed in with the baggage in the Jim Crow car with the other colored passengers with their babies and boxes of fried chicken and boiled eggs and their belongings overflowing from paper bags in the overhead compartment. The train pulled out of the station at last, and Ida Mae was on her way out of Chickasaw County and out of the state of Mississippi for the first time in her life.

the Illinois Central, along with the Atlantic Coast Line and Seaboard Air Line railroads, running between Florida and New York, and the Southern Pacific, connecting Texas and California, had become the historic means of escape, the Overground Railroad for slavery’s grandchildren.

The story played out in virtually every northern city—migrants sealed off in overcrowded colonies that would become the foundation for ghettos that would persist into the next century. These were the original colored quarters—the abandoned and identifiable no-man’s-lands that came into being when the least-paid people were forced to pay the highest rents for the most dilapidated housing owned by absentee landlords trying to wring the most money out of a place nobody cared about.

The South Side (Chicago) would become almost totally black and the North Side almost totally white. Ida Mae’s adopted home would become one of the most racially divided of all American cities and remain so for the rest of the twentieth century.

he had gone from the mind-numbing sameness of picking cotton to the mind-numbing sameness of turning a lever or twisting a widget or stoking a flame

The expectation that any colored woman walking in the white section of town was available to scrub floors and wash windows would continue into the 1960s,

West Rim Trail near Taos, NM – Well this day turned out to be…interesting. I’ll explain later. There are miles upon miles of trails on top of and into the Rio Grande Gorge near Taos. Some of them were made by automobiles in the early part of the 20th century before land protections set in. Some of them were/are made by bighorn sheep as they bound in and out of the gorge on a daily basis. I would someday love to hike all of them. The West Rim trail is around 10 miles and skirts the rim of the canyon from the Gorge Bridge at Highway 64 down to a parking lot near the 567 road where you can drive down to the river. I parked near this 567 road (which is near the Petaca Point trail I described in my February 2024 blog). From here I walked around 5 miles north along the rim. Some of the views are spectacular. I never tired of heading off trail towards the rim for great views of the steep cliffs and ribbon of Rio Grande below with its class IV rapids.

One of my goals for the day was to see if the Powerline Trail was walkable to the bottom of the canyon. It shows up on maps, but I couldn’t find any written articles about it. The good news is that I found the “trail”. It looks like there hadn’t been anyone on it for years. I slipped and slid down a small arroyo until I encountered a class 4 scramble that I wasn’t willing to try on my own. Beyond this scramble you could sort of see the remnants of a trail, but it would be a big adventure day with plenty of support needed in order to make it to the bottom. I headed back up the arroyo, but instead of getting back on the main trail from here I decided to follow a faint sheep trail for around a half mile just because it was so close to the rim with such incredible scenery (make sure you stop before you gaze out or you may find yourself at the bottom faster than you’d like). After a total of nearly 5 miles of wandering around I decided to head back on the main trail to my car.

Here's where the interesting part happens. I reached in my pocket to get my keys…no keys. Heart thump. I remember turning around at the trailhead at the start of the hike to make sure the car was locked, so I knew my keys were in my pocket at that point. The question was, where were they now? I had no time (nor energy) to rehike the 9 plus miles in search of them. I scoured the area around the trailhead, no luck. Finally called my daughter who drove the half hour out to rescue me. Luckily there was phone service otherwise it would have been even more interesting. I came up with 3 different places where my keys could have fallen out: two rocks where I had unlaced my shoes to get dirt out and that arroyo that I was slipping in and out of. I called my son and asked him to ship my spare key, which was in Colorado, just in case. We decided that I would come back the next morning with my daughter’s mountain bike to search for the keys. This would be my first ever mountain bike adventure. Granted, it’s mainly a flat trail, but still, my butt was not used the torture of that cruel mountain bike "seat" (who invented those…the Nazis?). So, my daughter kindly dropped me off before her work the next day and wished me luck (and took a photo of me on my first mountain bike adventure…she was very excited for me).

I headed off slowly, gazing only at the trail, looking for my keys. There could have been dozens of bighorn sheep and mountain lions all around me, but I never would have seen them as hard as I was concentrating on my search. I found so many shiny tin cans! I expected to find the keys at one of the three areas I mentioned. So eventually I quickened my pace towards those areas. I got to the Powerline trail arroyo first and scoured the area for maybe half an hour. No luck. On to the shoe-changing rocks (luckily, I had recorded my hike, so I had the exact track of the previous day). No luck at either rock. So, I slowly retraced my hike (this time on a mountain bike with its torturous seat). No luck, no luck, no luck. I was starting to come to the realization that I would have to wait for the spare key my son was sending. Remember that half mile of sheep trail I took? I got off the mountain bike and walked the bike along that precarious trail and a few yards in, there in the mud, was not a shiny tin can, but my car keys! Needle in a haystack euphoria moment there folks. It was then that I remembered slipping in the mud the previous day and nearly falling, but recovered. My best guess is that I had my hands in my pockets when I slipped, the keys fell out, and a new adventure was born.

I immediately called my son to cancel the next day shipment of my spare key (I caught him just as he was leaving for the post office). Then I called my daughter to tell her she didn’t have to pick me up and I would drive her mountain bike back in my car, with my muddy keys. It’s the first time in 50 years of hiking that I’ve lost my keys. I’m 66 years old and still learning lessons. This lesson: keep my keys in a zipped pocket from now on (or on a secure hook in my daypack), and maybe put an air tag on them.

Creation Lake by Rachel Kushner – A finalist for the 2024 Booker Prize, Creation Lake is a welcome change after reading five fairly heavy nonfiction books in a row. The story follows Sadie Smith, an undercover agent working under that assumed name in order to uncover any potential violent plots by an anarchist group in rural France. Sadie is on top of her game throughout the book as she infiltrates the anarchist organization by striking up a romantic relationship with a friend of the group’s leader months prior (she plays a long game). She manipulates this romantic lover along with his friends in order to make the relationship believable enough to get access to the group in rural France. Sadie is the narrator, and she leads you through some of her past operations, including one in which she ended up being fired by the FBI for losing an entrapment case against an eco-terrorist group. She’s working as a sort of free lance spy now for various private organizations, in this case likely for a big agricultural company operating in France.

Pascal, the group leader meets her in a small village to talk about his group and their philosophy. She is posing not only as his friend’s lover, but also as a language translator, and Pascal wants the group’s library translated into English. Her translation/spy work brings her into contact with some fascinating characters with a passion for living a simple life and rejecting capitalism. Pascal’s mentor, Bruno, is living in a cave somewhere in the area. He has rejected any further protesting and violence and instead shares his philosophy via email with Pascal and his compatriots. Although Bruno seems to be going off the deep end, he has some fascinating views of life and of the interconnectedness of past lives going back to the Neanderthals. Sadie (and I) enjoyed reading his philosophical ramblings.

Eventually Sadie gets wind of a protest at the fall festival. Farmers plan to dump milk on the highway and block traffic. But Sadie ends up doing some shady things to try and spur increased violence during the protest so that she can earn her paycheck (you start to see how she lost her entrapment case and was fired by the FBI). Things don’t go as planned even though Sadie manages to get away without getting caught. But the job has taken a toll and she takes a break from her spy work for a while, trying to determine what life is all about. But in the end Sadie is a cold-blooded spy and will continue this work, possibly in a future Rachel Kushner novel. I enjoyed reading about the history of the area (Neanderthals, World War II, the 1968 riots, etc.), but mainly I enjoyed watching Sadie do her thing with cold-hearted precision. Here are some lines:

There were glass jars of jellied meats that look like cat food, and which French people call a “terrine” and eat as if it were not cat food.

And then he leaned in like billions before him have done, acting upon a desire to kiss some woman. In such a scene between new lovers, a moment repeated everywhere all the time with no originality to it— none—Lucien surely felt that something singular and novel was taking place.

why would you want to survive mass death? What would be the purpose of life, if life were reduced to a handful of armed pessimists hoarding canned foods and fearing each other?

In a bunker, you cannot hear the human community in the earth, the deep cistern of voices, the lake of our creation.

Nature doesn’t bother me. What bothers me in nature is the possibility of people.

People who change affinities are the same kinds of people who are attracted to the permanence of tattoos.

this is what I knew: Life goes on a while. Then it ends. There is no fairness. Bad people are honored, and good ones are punished. The reverse is also true. Good people are honored, and bad people are punished, and some will call this grace, or the hand of God, instead of luck. But deep down, even if they lack the courage to admit it, inside each person, they know that the world is lawless and chaotic and random.

I was from the US, which to the library theorists was a mythical place of social extremes and gun violence.

“He drinks with these guys who are yelling about Arabs and foreign workers,” Alexandre said. I kept my face blank, to suppress my amusement. Refined and Parisian Alexandre had never been forced to associate with the sort of lower-class white people who might feel threatened, if misguidedly, by immigrants and nonwhites.

We want Catholic neighbors.’ And when they say Catholic they mean French, and by French they mean white.

The video was from one of those talk shows they have only in France, where people think writers are interesting

The man turned and put his hand on her arm, an ancient gesture employed in every epoch of history by gullible men attempting to calm strident women beset by reasonable doubts.

The Air They Breathe by Debra Hendrickson – In my never ending search to find ways to convince people (mainly conservatives) that climate change is real, I tend to look for places we can agree, then slowly present the brutal facts confronting the world. But, you know, sometimes you just have to get it all out and say it like it is. The wonderful Emily Atkin from the Heated newsletter says it like it is. And the author of this book, Debra Hendrickson says it like it is. Their anger tends to put off conservatives who will look for every excuse to believe the disinformation fueled by some fossil fuel companies and some ideologists. But if you can’t get angry when you see children being impacted by the results of climate change every day, then when can you get angry?

Hendrickson is a pediatrician based in Reno, Nevada, the US city that is heating up faster than any other. In her previous life she was an Environmental Studies major in college and went to graduate school in Forestry. So, she has a great underpinning for writing this book. But it’s her work in dealing with children impacted by the polluted air from the mega fires west of her town that drove her to write this powerful book which sparked reviews like this: “Reading The Air They Breathe brought me to tears”- Moms Clean Air Force; “…she points out the decades of failure by the world to take fossil fuel pollution and climate change seriously.” - The Daily Kos; “The climate crisis is a health crisis, and it is a health crisis, first and foremost, for children.” – Porchlight Books; "Pediatricians are among the most trusted people in our society, and this fine book reminds us why: they care about the most vulnerable, in very specific and useful ways. This book imagines that caring on a scale big enough to change the world." - Bill McKibben.

In this short (under 200 pages) but impactful book she addresses the following areas of climate change’s impact on children: Air pollution from mega fires, heatstroke risk in warming cities like Phoenix, flooding impacts in hurricane-ravaged Houston, vector borne diseases (like zika and malaria) becoming more common in a warming world, and the mental/emotional impacts of all of these. The section on heat in Phoenix was near and dear to my heart since I lived there for 40 years. I hiked those trails in the summer where she described the horrifying effects of heatstroke on young bodies. The parents of one child who died on the Apache Wash trail tried for years to close down trails during the summer; they were fought tooth and nail until rescue workers started getting impacted during heat rescues. Now the city has finally made the decision to close many trails during extreme heat. I probably would have been one fighting to keep the trails open, until I read about these kids. Here are some lines:

Wildfires, hurricanes, and heat waves make headlines. Small moments with my patients never will. But what is happening in my clinic tells another story of this strange and unsettling time. Children are bearing the weight, in their lungs and hearts and minds, of our madness.

It’s no wonder fossil fuel companies found it easy to confuse the public with propaganda denying climate change; the wonder is how their own hearts allowed it.

The amount of lung development that occurs after birth is one reason children are so vulnerable to environmental harm, and underscores how inseparable a child’s body is from the surrounding world.

“Fire season” had joined “flu season” on my mental calendar of cyclical illness, and I had begun to dread the warmest months—previously a time when my schedule slowed.

New research points to particle pollution as a risk factor for both autism and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)… Though autism and ADHD are complex disorders with multiple causes both genetic and environmental, a growing body of science indicates that air pollution—caused by fossil fuels and worsening due to climate change—is contributing to the rise of these conditions.

“Prior to 1960,” one medical historian noted, “most textbooks of pediatrics did not regard asthma as common let alone epidemic.” The percentage of American children with the disease almost tripled from 1980 to 2010— This rapid rise was part of a pattern. All atopic diseases—asthma, allergies, and eczema—jumped dramatically in those decades.

Over 9,200 American high school athletes are sickened annually by heat; their ER visits for heat illness have more than doubled since the late 1990s.

twenty-two weather-related billion-dollar events struck the US in 2020 alone, a new record. 2023 broke the record again, with twenty-five billion-dollar weather disasters that stretched from the tragic wildfire in Maui to historic flooding in Vermont.

When today’s grandparents were children themselves, the most sophisticated tool available to meteorologists was the weather balloon. That changed dramatically on April 14, 1969, when NASA quietly launched a satellite called the Nimbus 3. For the first time, human beings would be able to forecast the weather from far above Earth—

A century ago in the US, for example, 40 percent of all deaths were children under five, mostly due to infectious diseases. But by 2018—thanks to vaccines and other public health advances like clean drinking water, antibiotics, pasteurized milk, and mosquito control—only 2 percent of American deaths were babies and small children,

Solon is in Johnson County, which in recent years has had the most Lyme cases in Iowa. But two decades ago the disease was extremely rare here; it has increased twentyfold since 2000, far faster than the population has grown. Across Iowa and the US, Lyme cases tripled in the same period.

It’s a story repeated over and over: when we try to kill a microorganism with chemicals, there will be members of that species who are just slightly genetically different, and are not killed. Over time, as their susceptible brethren die off, these resistant organisms become more numerous and then dominate. Doctors soon find themselves without the weapons we had relied on.

Although America has contributed more CO2 to the atmosphere than any other country, its emissions peaked in 2005 at 6 gigatons per year and have fallen since, largely due to the retirement of coal plants for natural gas and wider adoption of wind and solar power.

green energy and sustainable living are as important to my patients’ welfare as car seats, medications, laboratory tests, and vaccines. Again, children’s bodies and minds are inseparable from the atmosphere. Its health and theirs are linked. The toxins we dump upward, and the steps we take to end that practice, will hugely impact their lives

Action breaks us out of despair and inertia. It gives us a sense of agency over this global crisis that we might otherwise surrender to

Surely our voices produce more than sound. Surely our science will yield more than a chronicle of our end. Because climate change has a face, and it is a child’s.

South Boulder Creek/Big Bluestem loop near Boulder – Today was the first day when the high temperature had made it out of the teens or twenties for a week. I had been hunkered down at home doing indoor projects while my leg muscles turned to frozen Jell-O. So, I was very excited to finally get outdoors. It was still snowing in the mountains, so I decided to check off a few more Boulder Open Space trails. I put together a loop from the directionally mouthful South Boulder Creek West trailhead. I stitched together the South Boulder Creek West, Mesa, and the Upper and Lower Big Bluestem trails for this 7-mile walk, of which about half was brand new ground for me. The snow hadn’t melted yet due to the low temperatures and there was between 2 and 4 inches for most of the walk, easy enough to do without spikes and not enough for snowshoes. There are several of these, what I call prairie to pines walks in the Boulder area. The hike starts in the open prairie with great views of the Flatirons, and then gradually rises up into the pine trees at the foot of the mountains along the Mesa trail. It was in the mid-30s for most of the walk and the sun finally came out about halfway through and just lit up the red rocks around the Flatirons. Combined with the snow, it made for a very pretty walk the whole way. There were a few runners and dog walkers out today, but quiet for the Boulder area. And I saw four big bull elk! That surprised me. I had seen elk once before on a Boulder area walk, but it’s pretty unusual, as they are normally up by Estes Park or Carter Lake during the winter. It was a pretty winter day but my unused legs were tired by the end and I was happy to get back to my car for the drive home.

Canyon Dreams: A Basketball Season on the Navajo Nation by Michael Powell - Both our kids played high school sports, so we've seen first hand the joys and pressures that sports brings to young kids. Imagine that pressure stretching out to include the hopes and dreams of an entire nation; in this case the Navajo Nation. I caught a glimpse of what is called rez ball (so called due to it being played on the Native American reservations) when our daughter played basketball in the 3A division in Arizona. Her little team of short white girls which normally had only parents and family watching their home games would travel to Tuba City or Whiteriver to play and there would be 5,000 Navajos in the stands cheering their teams on (boys and girls). It was crazy. I would sometimes go to see the semi-finals and finals held in the Phoenix Suns arena and when a 'rez team was in the tournament, the crowd doubled in size as streams of vehicles headed down to Phoenix from the small towns and villages in northeastern Arizona. So I was familiar with the phenomenon known as 'rez ball and that's what made this book seem so compelling to me. It's terrific.

Until next month, happy reading and rambling!

Before the Great Migration 90% of African Americans lived in the South. By the end, only 50% did so. The Great Migration eventually resulted in the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s, which in turn helped to improve life for those left behind in the South (although some would argue that it’s not fully recovered yet). The Great Migration ended mainly because of those Civil Rights heroes of the 1960s. I can understand why someone would not want to read a 622-page history book, but I assure you that this does not read like a normal history book. Wilkerson’s storytelling is gripping. If you decide not to read this book, then at least check out her 17-minute Ted Talk here.

I’ve read that several high schools and universities have incorporated this book into their curricula. I think everyone should read it. It’s that good. Hopefully the book’s usage in schools survives the next four years. Here are some lines:

A railing divided the stairs onto the train, one side of the railing for white passengers, the other for colored, so the soles of their shoes would not touch the same stair.

They were all stuck in a caste system as hard and unyielding as the red Georgia clay, and they each had a decision before them. In this, they were not unlike anyone who ever longed to cross the Atlantic or the Rio Grande.

“If it is necessary, every Negro in the state will be lynched,” James K. Vardaman, the white supremacy candidate in the 1903 Mississippi governor’s race, declared. He saw no reason for blacks to go to school. “The only effect of Negro education,” he said, “is to spoil a good field hand and make an insolent cook.” Mississippi voted Vardaman into the governor’s office and later sent him to the U.S. Senate.

Fifteen thousand men, women, and children gathered to watch eighteen-year-old Jesse Washington as he was burned alive in Waco, Texas, in May 1916. The crowd chanted, “Burn, burn, burn!” as Washington was lowered into the flames. One father holding his son on his shoulders wanted to make sure his toddler saw it. “My son can’t learn too young,” the father said.

(Warning: Graphic Detail): in the fall of 1934, when George was a teenager and old enough to take note of such things, perhaps the single worst act of torture and execution in twentieth-century America occurred in the panhandle town of Marianna, Florida…That October, a twenty-three-year-old colored farmhand named Claude Neal was accused of the rape and murder of a twenty-year-old white woman named Lola Cannidy…his captors took knives and castrated him in the woods. Then they made him eat the severed body parts…Around Neal’s neck, they tied a rope and pulled it over a limb to the point of his choking before lowering him to take up the torture again. “Every now and then somebody would cut off a finger or toe,” the witness said. Then the men used hot irons to burn him all over his body in a ritual that went on for several hours. Soon afterward, it was learned that Neal and the dead girl, who had known each other all their lives, had been lovers and that people in her family who discovered the liaison may have been involved in her death for the shame it had brought to the family.

In Louisiana in the 1930s, white teachers and principals were making an average salary of $1,165 a year. Colored teachers and principals were making $499 a year…The layers of accumulated assets built up by the better-paid dominant caste, generation after generation, would factor into a wealth disparity of white Americans having an average net worth ten times that of black Americans by the turn of the twenty-first century

the truth hit Pershing, too. He stepped outside himself and considered the absurdity that he was doing surgery for the United States Army and couldn’t operate in his own hometown.

They were packed in with the baggage in the Jim Crow car with the other colored passengers with their babies and boxes of fried chicken and boiled eggs and their belongings overflowing from paper bags in the overhead compartment. The train pulled out of the station at last, and Ida Mae was on her way out of Chickasaw County and out of the state of Mississippi for the first time in her life.

the Illinois Central, along with the Atlantic Coast Line and Seaboard Air Line railroads, running between Florida and New York, and the Southern Pacific, connecting Texas and California, had become the historic means of escape, the Overground Railroad for slavery’s grandchildren.

The story played out in virtually every northern city—migrants sealed off in overcrowded colonies that would become the foundation for ghettos that would persist into the next century. These were the original colored quarters—the abandoned and identifiable no-man’s-lands that came into being when the least-paid people were forced to pay the highest rents for the most dilapidated housing owned by absentee landlords trying to wring the most money out of a place nobody cared about.

The South Side (Chicago) would become almost totally black and the North Side almost totally white. Ida Mae’s adopted home would become one of the most racially divided of all American cities and remain so for the rest of the twentieth century.

he had gone from the mind-numbing sameness of picking cotton to the mind-numbing sameness of turning a lever or twisting a widget or stoking a flame

The expectation that any colored woman walking in the white section of town was available to scrub floors and wash windows would continue into the 1960s,

West Rim Trail near Taos, NM – Well this day turned out to be…interesting. I’ll explain later. There are miles upon miles of trails on top of and into the Rio Grande Gorge near Taos. Some of them were made by automobiles in the early part of the 20th century before land protections set in. Some of them were/are made by bighorn sheep as they bound in and out of the gorge on a daily basis. I would someday love to hike all of them. The West Rim trail is around 10 miles and skirts the rim of the canyon from the Gorge Bridge at Highway 64 down to a parking lot near the 567 road where you can drive down to the river. I parked near this 567 road (which is near the Petaca Point trail I described in my February 2024 blog). From here I walked around 5 miles north along the rim. Some of the views are spectacular. I never tired of heading off trail towards the rim for great views of the steep cliffs and ribbon of Rio Grande below with its class IV rapids.

One of my goals for the day was to see if the Powerline Trail was walkable to the bottom of the canyon. It shows up on maps, but I couldn’t find any written articles about it. The good news is that I found the “trail”. It looks like there hadn’t been anyone on it for years. I slipped and slid down a small arroyo until I encountered a class 4 scramble that I wasn’t willing to try on my own. Beyond this scramble you could sort of see the remnants of a trail, but it would be a big adventure day with plenty of support needed in order to make it to the bottom. I headed back up the arroyo, but instead of getting back on the main trail from here I decided to follow a faint sheep trail for around a half mile just because it was so close to the rim with such incredible scenery (make sure you stop before you gaze out or you may find yourself at the bottom faster than you’d like). After a total of nearly 5 miles of wandering around I decided to head back on the main trail to my car.

Here's where the interesting part happens. I reached in my pocket to get my keys…no keys. Heart thump. I remember turning around at the trailhead at the start of the hike to make sure the car was locked, so I knew my keys were in my pocket at that point. The question was, where were they now? I had no time (nor energy) to rehike the 9 plus miles in search of them. I scoured the area around the trailhead, no luck. Finally called my daughter who drove the half hour out to rescue me. Luckily there was phone service otherwise it would have been even more interesting. I came up with 3 different places where my keys could have fallen out: two rocks where I had unlaced my shoes to get dirt out and that arroyo that I was slipping in and out of. I called my son and asked him to ship my spare key, which was in Colorado, just in case. We decided that I would come back the next morning with my daughter’s mountain bike to search for the keys. This would be my first ever mountain bike adventure. Granted, it’s mainly a flat trail, but still, my butt was not used the torture of that cruel mountain bike "seat" (who invented those…the Nazis?). So, my daughter kindly dropped me off before her work the next day and wished me luck (and took a photo of me on my first mountain bike adventure…she was very excited for me).

I headed off slowly, gazing only at the trail, looking for my keys. There could have been dozens of bighorn sheep and mountain lions all around me, but I never would have seen them as hard as I was concentrating on my search. I found so many shiny tin cans! I expected to find the keys at one of the three areas I mentioned. So eventually I quickened my pace towards those areas. I got to the Powerline trail arroyo first and scoured the area for maybe half an hour. No luck. On to the shoe-changing rocks (luckily, I had recorded my hike, so I had the exact track of the previous day). No luck at either rock. So, I slowly retraced my hike (this time on a mountain bike with its torturous seat). No luck, no luck, no luck. I was starting to come to the realization that I would have to wait for the spare key my son was sending. Remember that half mile of sheep trail I took? I got off the mountain bike and walked the bike along that precarious trail and a few yards in, there in the mud, was not a shiny tin can, but my car keys! Needle in a haystack euphoria moment there folks. It was then that I remembered slipping in the mud the previous day and nearly falling, but recovered. My best guess is that I had my hands in my pockets when I slipped, the keys fell out, and a new adventure was born.

I immediately called my son to cancel the next day shipment of my spare key (I caught him just as he was leaving for the post office). Then I called my daughter to tell her she didn’t have to pick me up and I would drive her mountain bike back in my car, with my muddy keys. It’s the first time in 50 years of hiking that I’ve lost my keys. I’m 66 years old and still learning lessons. This lesson: keep my keys in a zipped pocket from now on (or on a secure hook in my daypack), and maybe put an air tag on them.

|

| Rio Grande winding its way south |

|

| I was hiking on that plateau in the middle right last year |

|

| Very cool cloud formations |

|

| Viewing the mountains from the desert |

|

| Kevin has a great view for eternity up on the rim |

|

| Taos mountains beyond the rim |

|

| Casting a long shadow on this rock peninsula |

|

| Rim and mountains |

|

| Heading out on my first mountain bike trip to find my keys |

|

| Found them! |

Pascal, the group leader meets her in a small village to talk about his group and their philosophy. She is posing not only as his friend’s lover, but also as a language translator, and Pascal wants the group’s library translated into English. Her translation/spy work brings her into contact with some fascinating characters with a passion for living a simple life and rejecting capitalism. Pascal’s mentor, Bruno, is living in a cave somewhere in the area. He has rejected any further protesting and violence and instead shares his philosophy via email with Pascal and his compatriots. Although Bruno seems to be going off the deep end, he has some fascinating views of life and of the interconnectedness of past lives going back to the Neanderthals. Sadie (and I) enjoyed reading his philosophical ramblings.

Eventually Sadie gets wind of a protest at the fall festival. Farmers plan to dump milk on the highway and block traffic. But Sadie ends up doing some shady things to try and spur increased violence during the protest so that she can earn her paycheck (you start to see how she lost her entrapment case and was fired by the FBI). Things don’t go as planned even though Sadie manages to get away without getting caught. But the job has taken a toll and she takes a break from her spy work for a while, trying to determine what life is all about. But in the end Sadie is a cold-blooded spy and will continue this work, possibly in a future Rachel Kushner novel. I enjoyed reading about the history of the area (Neanderthals, World War II, the 1968 riots, etc.), but mainly I enjoyed watching Sadie do her thing with cold-hearted precision. Here are some lines:

There were glass jars of jellied meats that look like cat food, and which French people call a “terrine” and eat as if it were not cat food.

And then he leaned in like billions before him have done, acting upon a desire to kiss some woman. In such a scene between new lovers, a moment repeated everywhere all the time with no originality to it— none—Lucien surely felt that something singular and novel was taking place.

why would you want to survive mass death? What would be the purpose of life, if life were reduced to a handful of armed pessimists hoarding canned foods and fearing each other?

In a bunker, you cannot hear the human community in the earth, the deep cistern of voices, the lake of our creation.

Nature doesn’t bother me. What bothers me in nature is the possibility of people.

People who change affinities are the same kinds of people who are attracted to the permanence of tattoos.

this is what I knew: Life goes on a while. Then it ends. There is no fairness. Bad people are honored, and good ones are punished. The reverse is also true. Good people are honored, and bad people are punished, and some will call this grace, or the hand of God, instead of luck. But deep down, even if they lack the courage to admit it, inside each person, they know that the world is lawless and chaotic and random.

I was from the US, which to the library theorists was a mythical place of social extremes and gun violence.

“He drinks with these guys who are yelling about Arabs and foreign workers,” Alexandre said. I kept my face blank, to suppress my amusement. Refined and Parisian Alexandre had never been forced to associate with the sort of lower-class white people who might feel threatened, if misguidedly, by immigrants and nonwhites.

We want Catholic neighbors.’ And when they say Catholic they mean French, and by French they mean white.

The video was from one of those talk shows they have only in France, where people think writers are interesting

The man turned and put his hand on her arm, an ancient gesture employed in every epoch of history by gullible men attempting to calm strident women beset by reasonable doubts.

The Air They Breathe by Debra Hendrickson – In my never ending search to find ways to convince people (mainly conservatives) that climate change is real, I tend to look for places we can agree, then slowly present the brutal facts confronting the world. But, you know, sometimes you just have to get it all out and say it like it is. The wonderful Emily Atkin from the Heated newsletter says it like it is. And the author of this book, Debra Hendrickson says it like it is. Their anger tends to put off conservatives who will look for every excuse to believe the disinformation fueled by some fossil fuel companies and some ideologists. But if you can’t get angry when you see children being impacted by the results of climate change every day, then when can you get angry?

Hendrickson is a pediatrician based in Reno, Nevada, the US city that is heating up faster than any other. In her previous life she was an Environmental Studies major in college and went to graduate school in Forestry. So, she has a great underpinning for writing this book. But it’s her work in dealing with children impacted by the polluted air from the mega fires west of her town that drove her to write this powerful book which sparked reviews like this: “Reading The Air They Breathe brought me to tears”- Moms Clean Air Force; “…she points out the decades of failure by the world to take fossil fuel pollution and climate change seriously.” - The Daily Kos; “The climate crisis is a health crisis, and it is a health crisis, first and foremost, for children.” – Porchlight Books; "Pediatricians are among the most trusted people in our society, and this fine book reminds us why: they care about the most vulnerable, in very specific and useful ways. This book imagines that caring on a scale big enough to change the world." - Bill McKibben.

In this short (under 200 pages) but impactful book she addresses the following areas of climate change’s impact on children: Air pollution from mega fires, heatstroke risk in warming cities like Phoenix, flooding impacts in hurricane-ravaged Houston, vector borne diseases (like zika and malaria) becoming more common in a warming world, and the mental/emotional impacts of all of these. The section on heat in Phoenix was near and dear to my heart since I lived there for 40 years. I hiked those trails in the summer where she described the horrifying effects of heatstroke on young bodies. The parents of one child who died on the Apache Wash trail tried for years to close down trails during the summer; they were fought tooth and nail until rescue workers started getting impacted during heat rescues. Now the city has finally made the decision to close many trails during extreme heat. I probably would have been one fighting to keep the trails open, until I read about these kids. Here are some lines:

Wildfires, hurricanes, and heat waves make headlines. Small moments with my patients never will. But what is happening in my clinic tells another story of this strange and unsettling time. Children are bearing the weight, in their lungs and hearts and minds, of our madness.

It’s no wonder fossil fuel companies found it easy to confuse the public with propaganda denying climate change; the wonder is how their own hearts allowed it.

The amount of lung development that occurs after birth is one reason children are so vulnerable to environmental harm, and underscores how inseparable a child’s body is from the surrounding world.

“Fire season” had joined “flu season” on my mental calendar of cyclical illness, and I had begun to dread the warmest months—previously a time when my schedule slowed.

New research points to particle pollution as a risk factor for both autism and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)… Though autism and ADHD are complex disorders with multiple causes both genetic and environmental, a growing body of science indicates that air pollution—caused by fossil fuels and worsening due to climate change—is contributing to the rise of these conditions.

“Prior to 1960,” one medical historian noted, “most textbooks of pediatrics did not regard asthma as common let alone epidemic.” The percentage of American children with the disease almost tripled from 1980 to 2010— This rapid rise was part of a pattern. All atopic diseases—asthma, allergies, and eczema—jumped dramatically in those decades.

Over 9,200 American high school athletes are sickened annually by heat; their ER visits for heat illness have more than doubled since the late 1990s.

twenty-two weather-related billion-dollar events struck the US in 2020 alone, a new record. 2023 broke the record again, with twenty-five billion-dollar weather disasters that stretched from the tragic wildfire in Maui to historic flooding in Vermont.

When today’s grandparents were children themselves, the most sophisticated tool available to meteorologists was the weather balloon. That changed dramatically on April 14, 1969, when NASA quietly launched a satellite called the Nimbus 3. For the first time, human beings would be able to forecast the weather from far above Earth—

A century ago in the US, for example, 40 percent of all deaths were children under five, mostly due to infectious diseases. But by 2018—thanks to vaccines and other public health advances like clean drinking water, antibiotics, pasteurized milk, and mosquito control—only 2 percent of American deaths were babies and small children,

Solon is in Johnson County, which in recent years has had the most Lyme cases in Iowa. But two decades ago the disease was extremely rare here; it has increased twentyfold since 2000, far faster than the population has grown. Across Iowa and the US, Lyme cases tripled in the same period.

It’s a story repeated over and over: when we try to kill a microorganism with chemicals, there will be members of that species who are just slightly genetically different, and are not killed. Over time, as their susceptible brethren die off, these resistant organisms become more numerous and then dominate. Doctors soon find themselves without the weapons we had relied on.

Although America has contributed more CO2 to the atmosphere than any other country, its emissions peaked in 2005 at 6 gigatons per year and have fallen since, largely due to the retirement of coal plants for natural gas and wider adoption of wind and solar power.

green energy and sustainable living are as important to my patients’ welfare as car seats, medications, laboratory tests, and vaccines. Again, children’s bodies and minds are inseparable from the atmosphere. Its health and theirs are linked. The toxins we dump upward, and the steps we take to end that practice, will hugely impact their lives

Action breaks us out of despair and inertia. It gives us a sense of agency over this global crisis that we might otherwise surrender to

Surely our voices produce more than sound. Surely our science will yield more than a chronicle of our end. Because climate change has a face, and it is a child’s.

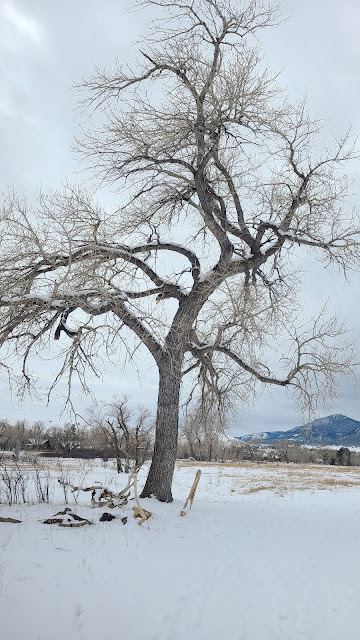

South Boulder Creek/Big Bluestem loop near Boulder – Today was the first day when the high temperature had made it out of the teens or twenties for a week. I had been hunkered down at home doing indoor projects while my leg muscles turned to frozen Jell-O. So, I was very excited to finally get outdoors. It was still snowing in the mountains, so I decided to check off a few more Boulder Open Space trails. I put together a loop from the directionally mouthful South Boulder Creek West trailhead. I stitched together the South Boulder Creek West, Mesa, and the Upper and Lower Big Bluestem trails for this 7-mile walk, of which about half was brand new ground for me. The snow hadn’t melted yet due to the low temperatures and there was between 2 and 4 inches for most of the walk, easy enough to do without spikes and not enough for snowshoes. There are several of these, what I call prairie to pines walks in the Boulder area. The hike starts in the open prairie with great views of the Flatirons, and then gradually rises up into the pine trees at the foot of the mountains along the Mesa trail. It was in the mid-30s for most of the walk and the sun finally came out about halfway through and just lit up the red rocks around the Flatirons. Combined with the snow, it made for a very pretty walk the whole way. There were a few runners and dog walkers out today, but quiet for the Boulder area. And I saw four big bull elk! That surprised me. I had seen elk once before on a Boulder area walk, but it’s pretty unusual, as they are normally up by Estes Park or Carter Lake during the winter. It was a pretty winter day but my unused legs were tired by the end and I was happy to get back to my car for the drive home.

|

| Day started out gray and cloudy but with great views of the Flatirons |

|

| I'll be heading up into those foothills |

|

| Lots of trees clambering for my attention today |

|

| Bull elk chillin' |

|

| Trail art |

|

| Entering the foothills with more snow |

|

| Sun shining on red rock formations |

|

| Pretty winter scene |

|

| Perfectly coated tree |

|

| Back out on the prairie with last views of the Flatirons |

Canyon Dreams: A Basketball Season on the Navajo Nation by Michael Powell - Both our kids played high school sports, so we've seen first hand the joys and pressures that sports brings to young kids. Imagine that pressure stretching out to include the hopes and dreams of an entire nation; in this case the Navajo Nation. I caught a glimpse of what is called rez ball (so called due to it being played on the Native American reservations) when our daughter played basketball in the 3A division in Arizona. Her little team of short white girls which normally had only parents and family watching their home games would travel to Tuba City or Whiteriver to play and there would be 5,000 Navajos in the stands cheering their teams on (boys and girls). It was crazy. I would sometimes go to see the semi-finals and finals held in the Phoenix Suns arena and when a 'rez team was in the tournament, the crowd doubled in size as streams of vehicles headed down to Phoenix from the small towns and villages in northeastern Arizona. So I was familiar with the phenomenon known as 'rez ball and that's what made this book seem so compelling to me. It's terrific.

Powell, a Pulitzer prize winning New York Times columnist followed the Chinle Wildcats basketball team during its 2017-2018 season. But this story is more than just about basketball. As NPR wrote in its 2019 review: "...it's his deep dives into the lives of those associated with Chinle and its high school that sets Canyon Dreams apart. He profiles not just the players and coaching staff, but also teachers, townspeople and activists, and the result is a moving portrait of what it's like to live on the reservation." The stories of the families of the players and of other Navajo are what enthralled me as much as the gripping story of the team's drive for a state championship. He captured the poverty, alcoholism, and unemployment of the region as well as he captured the mysticism, activism, and joy of the people. I especially enjoyed his encounter with Rita Bilagody, a Navajo woman who nearly singlehandedly stopped a developer from ruining the confluence of the Colorado and Little Colorado Rivers. I remember buying a shirt to support her effort that said "Save the Confluence" on it. I wore it proudly and was elated that the Navajo Nation voted to reject the development on their sacred ground.

But the star (among many) of the book is the 70 year old coach, Raul Mendoza. He was a legend in small town basketball in Arizona, winning over 700 games in his career, including a state championship with Holbrook. He wanted to bring a state championship to Chinle, but he cared as much about the boys as individuals as he did for the team as a whole. He was a guidance councilor in his past and he brought that compassion with him as coach. It certainly wasn't for the $5,000 salary high school coaches made that he worked so hard. He wanted these kids to taste success and to know how to handle defeat because he always stressed that basketball is hard, but so is life. Here are some lines:

Four thousand people live in Chinle, and on midwinter nights five thousand crowded into the Wildcat

Den for big games.

There was something shimmering and glistening and alive about rez ball, a joyous snaking pell-mell

speed. Dribbles and passes flew about in riffs as if in a jazz improvisation. Running was woven into

everything. The boys did not stop, ever.

Booze bewitches the Navajo Nation, and Gallup, New Mexico, has more liquor stores per capita than any

place in the Southwest. The road between Window Rock and Gallup is known as the “highway of death.”

Mendoza brought up a charged subject: the future. What do you want from your life? When you

graduate, will you be content to hang out at Bashas’ supermarket and go to the Navajo Fair each

September and live at home and wait for Grandma’s government check? Do you want more than that?

“You are not floating alone,” (Mendoza) told Zackary. “Stay in school and hold tight to your little brother. These

troubles of yours are not the sum of your life. God’s children are not a tragedy, and your life is not

doomed.”

The little man slipped

into jeans and his STRAIGHT OUTTA CHINLE T-shirt and sneakers and walked back to the basketball

floor.

They ration water for drinking, baths, dishes; per-capita

water use on the reservation is a tiny fraction of what it is elsewhere in the United States.

“Have you seen Wind River?” a young man asked me. The film offered a chilly and brutal take on

reservation life. “That’s us. That’s our story.” (Wind River is a great movie...check it out sometime)

A Navajo did not see himself as master of this landscape; he was part of it, in its harshness and its

beauty.

Before the developer could get into his SUV, before he could drive back to the Valley of the Sun, Rita

walked over to him and made sure her eyes caught his like flies stuck in ointment. She expected he

would try again. Powerful white men rarely accepted defeat with grace. “You’ve gotten a taste of what

we can do,” she told him. “We’ll do it again.”

Nachae Nez recalled a game against a fierce rival last year. He sat on the Wildcats bench before the

game, his head lowered, girding for the struggle. He felt fingers run across his scalp, and when he spun

around, he saw an older man with a not-so-friendly grin disappear into the crowd. His scalp began to

burn as though fire ants were racing back and forth.

In the Anglo world, stories run linear. We Navajo locate ourselves in timelessness.

To trace the Diné roots was to go back to Tibet and Siberia in high

mountain valleys and along the forested coves of Lake Baikal.

Cecil kicked it and traveled as a lay preacher, wandering north to Yellowknife, in the forested vastness

of the Northwest Territories, where he preached God’s word to the Athabascan. One late night near the

Arctic Circle, he called Ted, his exuberance a knife cutting through that scratchy telephone line: “Ted, it’

s Cee! You’re not going to believe this! They speak the same language we do. We understand each other.

We really are cousins!”

The day before the semifinals, a great migration of cars and SUVs and trucks edged down US Highway

191 and along those old Indian routes, thousands of fans driving south to Phoenix, the Second Rez, to

cheer on these Navajo boys.

Lindsay Ranch in Rocky Flats National Wildlife Refuge near Superior - From 1951 until 1992 the US Atomic Energy Commission made plutonium triggers (i.e. mini bombs) for nuclear weapons at Rocky Flats. The buffer zone around that facility is now a National Wildlife Refuge after a 10 year cleanup that included removal of 21 tons of weapons-grade material, removal of more than 1.3 million cubic meters of waste, including contaminated soil, treatment of more than 16 million gallons of water, and construction four groundwater treatment systems. Did I feel safe walking here? Eh, I guess? There were two major fires at the facility (1957 and 1969) and barrel leaks that spread radioactive contamination to a large part of Denver, but the public wasn't informed until sometime in the 1970s. In 1979 there were anti-nuke protests around the US, including 15,000 people protesting at Rocky Flats (Daniel Ellsburg and Allen Ginsberg were among those arrested here). I vaguely remembered them when I lived in Boulder in 1978 and 1979 on a college coop program. Protests continued throughout the 80s while the weapons were still being processed. It finally came to an end in 1989 with a raid by the FBI and subsequent charges and fines against the then-owner Rockwell (Dow Chemical was the original owner). The labs were shut down and the $7B cleanup effort ensued. It was declared a Superfund site (like the Love Canal in New York - see my review of Paradise Falls from August 2023). Multiple studies performed in the latter part of the 20th century showed significant cancer and other health issues among the Denver population downwind from the site. Even today there are disagreements about how much plutonium still exists, some groups calling the area a plutonium dust bowl. There is a housing development on the southern border of the area called Candelas that began building in 2019. My wife and I actually looked at buying a home in that area until we read about all of this. There are still groups claiming that the cleanup wasn't effective, and there are multiple conflicting reports about the contamination levels. It's hard to know if it will ever get resolved.

I decided I'd be OK wandering around here for a couple of hours, but I don't think I would bring my grandkids here...even though a sign at the trailhead says that you could visit the site hundreds of times in a year and get the same radiation level as a medical X-ray. Hmm, I hope so, but I doubt I'll set out to prove that. I walked about 6.5 miles along a couple of loops connected by a Rocky Mountain Greenway trail section. There really are tremendous views of the Flatirons from here, plus a nice highlight was seeing the remains of the Lyndsay Ranch in a pretty gully protected from the wind. George and Susan Lyndsay purchased the land in 1941 and their ranch hand lived in the buildings here until 1951 when the Atomic Energy Commission purchased it. It was really windy today, which is why I didn't want to head into the mountains. When it's blowing 30mph, I'd rather be in 60 degree weather than 30 degrees. I saw two trail runners and one mountain biker today. And lots of elk poop.

|

| Great views of the Flatirons from the prairie |

|

| Hmmm, a plutonium vent? |

|

| Part of the Rocky Mountain Greenway Trail |

|

| Abandoned Lyndsay Ranch in a quiet gully |

|

| Artsy old ranch shot |

|

| Ranch building |

|

| I loved this shot of a giant windmill blade peering up behind an old ranch |

|

| They had nice views |

|

| A lonely tree watching the wind blow in some weather |

|

| The sun was shining on the grass in an interesting way |

.jpg)